Warning: This is probably the most controversial post I’ve ever written, so if you don’t like having your toes trampled upon, you might want to stop reading right now. Or maybe you’ll agree with me. A lot of you won’t. I fully expect disgruntled readers, angry comments, hate mail, even (It’s beyondwaiting@yahoo.com, friends). I’m okay with that. Because I realize that, in this day and age, the “H” word is a little hard to swallow.

Yesterday afternoon, a friend linked to this post. I had a major problem with removing the word “hate” from my vocabulary, arguing that the moment we stop hating sin is the moment it swallows us up. The age old quote is “Love the Sinner, Hate the Sin.” It is possible to do both at the same time, I said. That’s when a helpful commenter linked me to this post.

I think that post was supposed to debate my point; I believe it only enforced it. Remember what I said about removing the word hate from our vocabulary? It looks to me like the author believed one thing until his brother was the one struggling. Now he’s changed his mind about hating the sin because it puts tension on his relationship with his brother?

I fully agree that we should not hold homosexuality to a different degree of sin, but I don’t think that means we need to brush it under the table. It ranks right there with idol worship, adultery, stealing, and a number of other sins (sorry if you don’t like my saying that, but Paul said it, too—1 Corinthians 6:9-11). A sin no greater than any others, but a sin just the same.

I understand why the author wants to quit believing his brother’s lifestyle is Biblically unacceptable. I’ve wanted to give up on my own beliefs before because it would have been so much easier to pretend everything was all right. It would be much less painful to just accept people as they are and not have to question their life choices. I’m sure my own brother wished the sting of conviction in my soul didn’t speak so loudly, because I know I wished his would shut up when the time came for him to turn the tables on me.

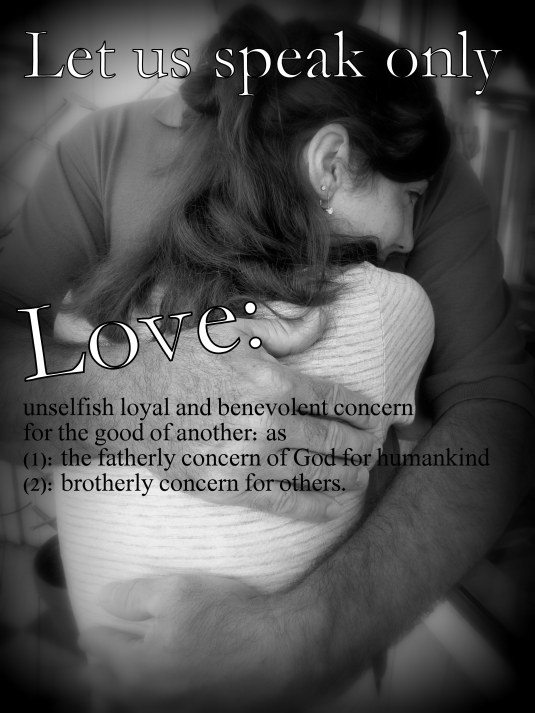

I think we’ve confused love and tolerance, thinking they are one and the same. But compare these definitions:

Tolerance: the ability or willingness to tolerate something, in particular the existence of opinions or behavior that one does not necessarily agree with.

Love: unselfish loyal and benevolent concern for the good of another: as (1) : the fatherly concern of God for humankind (2) : brotherly concern for others.

If I’m truly concerned for the good of another, I’m not going to simply “tolerate” their harmful habits. Because I don’t think loving the sinner and hating the sin are mutually exclusive.

Which brings me to the second point in Article #2. When writing of the adulterous woman, the author states:

But Jesus knelt with her in the sand. Unafraid to get dirty. Unafraid to affirm her humanity. “Neither do I condemn you, go and sin no more.”

He could have said “You’re a sinner, but I love you anyways.” But she knew she was a sinner. Those voices were loud and near and they held rocks above her head.

Um, Jesus kind of did tell her she was a sinner. It’s sort of implied in the phrase, “Go and sin no more.” Yes, He accepted her. Yes, He refused to throw rocks alongside the others, but He didn’t completely sweep her sin under the rug. He acknowledged it. He entreated her to leave it behind. To start new and afresh. Essentially, Jesus did say, “You’re a sinner, but I love you anyways.”

I think that’s where the Christians who are preaching grace are falling short. We’re looking the broken people of the world straight in the eye and saying, “Neither do I condemn you.” And that’s a beautiful thing. But we’re forgetting, always forgetting, to remind them to go and sin no more.

Maybe Jarrid Wilson was right, and people don’t know how to separate the sinner from the sin. Because, in accepting people, we’ve made it look like we’re accepting their sin. Or maybe we feel like we have to accept their sin in order to fully accept them.

I was once in a social setting where a friend asked another friend what her sister was doing these days.

“She’s doing really good,” the friend replied. “She’s living with her boyfriend in Columbus.”

“Oh, that’s cool.”

That’s cool? Does anyone else see a problem with that statement? Or was I the only one choking on my tongue? Those are the kinds of reports about my friends that I find disappointing, not because it makes me love them any less, but because I only wanted God’s best for them. I hate that they’ve walked away from that. Yes, hate.

Let’s bring it down a level. Imagine you have a kid, and of course you do what all good parents do and warn him away from the hot stove. But he’s a kid, and kids will do what kids are going to do. He touches the stove, he gets burned, what now? You’re probably going to pull him into your arms, stick his poor, little hand under the faucet, and whisper soothing platitudes like, “It’s okay, baby. You’re going to be all right. Mommy/Daddy loves you.”

All those things are good. All those things are true. But you know what else is probably going on in your mind? You probably hate that he disobeyed you; not because you’re hard-core authoritarian, but because he’s hurt. You probably hate that he got burned. You hate that he had to learn this lesson the hard way.

Does this distract from your love for him? Absolutely not.

Because love and hate are not mutually exclusive.

I love my parents, therefore I hate disappointing them.

I love my brother, therefore I hate watching him make poor choices.

I love my students, therefore I hate that many of them have so much hurt in their lives.

There is never a good time to speak hateful words to someone, but it’s okay—no, really, it’s for the best—to gently correct your brother when he has failed (and to allow your brother to correct you). It’s time to take our fallen brethren by the hand and truthfully say, “Neither do I condemn you, go and sin no more.”

Hate the sin. (No, really, hate it.) But speak the truth in love.